'Abandon every hope. ye who enter here'

Canto III - The Neutrals, Indifferent, and The Opportunists

"I know your works: you are neither cold nor hot. Would that you were cold or hot! So, because you are lukewarm, and neither cold nor hot, I will spew you out of my mouth."

- Revelation 3:15-16

Quick Note: The quotes I’m using are from both the Ciardi and Longfellow Translations of The Inferno. Which ones I decide to use depends on which lines I find more beautiful. That may not be acceptable in an academic setting…but luckily for me, I’m not an academic, nor do I pretend to be, nor do I ever wish to be considered one (no offense to those who are or pretend to be).

If you’re behind, here’s my post on Canto I and Canto II.

Now, let’s move on to the spiritually idle souls of Canto III (I worked hard to condense the length this time).

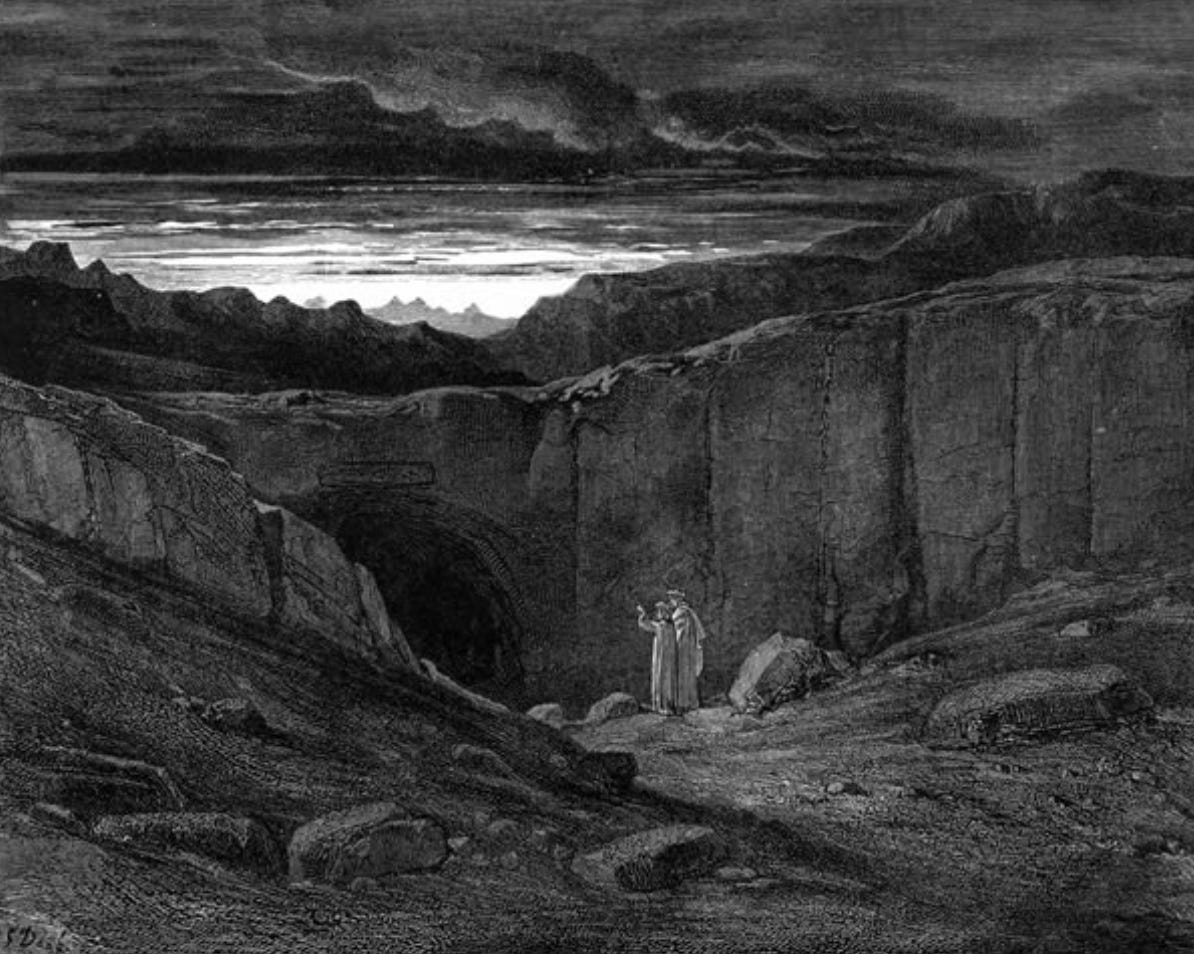

The Gates of Hell: Abandoning Hope

As Dante and Virgil approach the entrance to Hell in Canto III, they encounter one of the most famous and chilling passages in all of literature:

"Through me the way into the suffering city,

Through me the way to the eternal pain,

Through me the way that runs among the lost.Justice urged on my high artificer;

My maker was divine authority,

The highest wisdom, and the primal love.Before me nothing but eternal things

Were made, and I endure eternally.

Abandon every hope. ye who enter here."

This inscription above the gates of Hell establishes the tone and themes that will permeate Dante's journey through the Inferno. The repetition of "Through me" creates an ominous, incantatory effect, while personifying Hell itself as speaking directly to those who would enter. The gate proclaims itself as the way to "suffering," "eternal pain," and being "lost" - a stark warning of what lies ahead.

Yet the inscription also reveals deeper theological concepts. Hell is described as a place created by "Justice," "divine authority," and even "primal love." This presents the challenging idea that Hell, despite its horrors, is part of God's divine plan and even stems from His love. The reference to "eternal things" and Hell enduring "eternally" reinforces the concept of Hell as a permanent state, not a temporary punishment.

The final line—"Abandon every hope, ye who enter here"—is perhaps the most famous quote from the entire Divine Comedy. It presents Hell as a place of utter despair, where even the possibility of hope is extinguished. This abandonment of hope can be seen as the ultimate torment of Hell—to be cut off forever from God's grace and mercy.

Dante's reaction to this foreboding entrance reveals his very human trepidation:

"These words I saw were written in dark color

On the lintel of a gate; whereat I said:

'Master, their meaning is difficult for me.'"

His hesitation and confusion are entirely understandable when faced with such a daunting threshold. Virgil's gentle reassurance - "Here must all distrust be left behind; / All cowardice must here be put to death" - highlights his role as a guide and source of courage for Dante. This dynamic between the uncertain pilgrim and his wise guide will play out repeatedly throughout their journey.

The Vestibule of Hell: Those Who Lived Without Blame and Praise

After passing through the gate, Dante encounters a surprising group of souls in the vestibule of Hell:

"This miserable mode

Maintain the melancholy souls of those

Who lived withouten infamy or praise.Commingled are they with that caitiff choir

Of Angels, who have not rebellious been,

Nor faithful were to God, but were for self."

These are not lavish sinners but rather those who lived lives of moral apathy and neutrality. They took no strong stands in life, whether for good or evil. Their punishment is to eternally chase a blank banner while being stung by insects, symbolizing the futility of their noncommital lives.

This presents a challenging moral concept - that simply avoiding major sin is not enough to merit salvation. Dante suggests that failing to pursue virtue and make meaningful moral choices actively is itself a form of spiritual failure. The idea that even angels could be condemned for moral neutrality ("not faithful were to God,but were for self") further emphasizes this point.

Dante's reaction:

"And I, who looked again, beheld a banner,

Which, whirling around, ran on so rapidly,

That of all pause it seemed to me indignant;And after it there came so long a train

Of people, that I ne'er would have believed

That ever Death so many had undone."

His amazement at the vast number of these souls suggests that moral apathy and the failure to take meaningful stands are widespread human failings. This serves as a stark warning to readers about the dangers of passivity and lack of conviction in life.

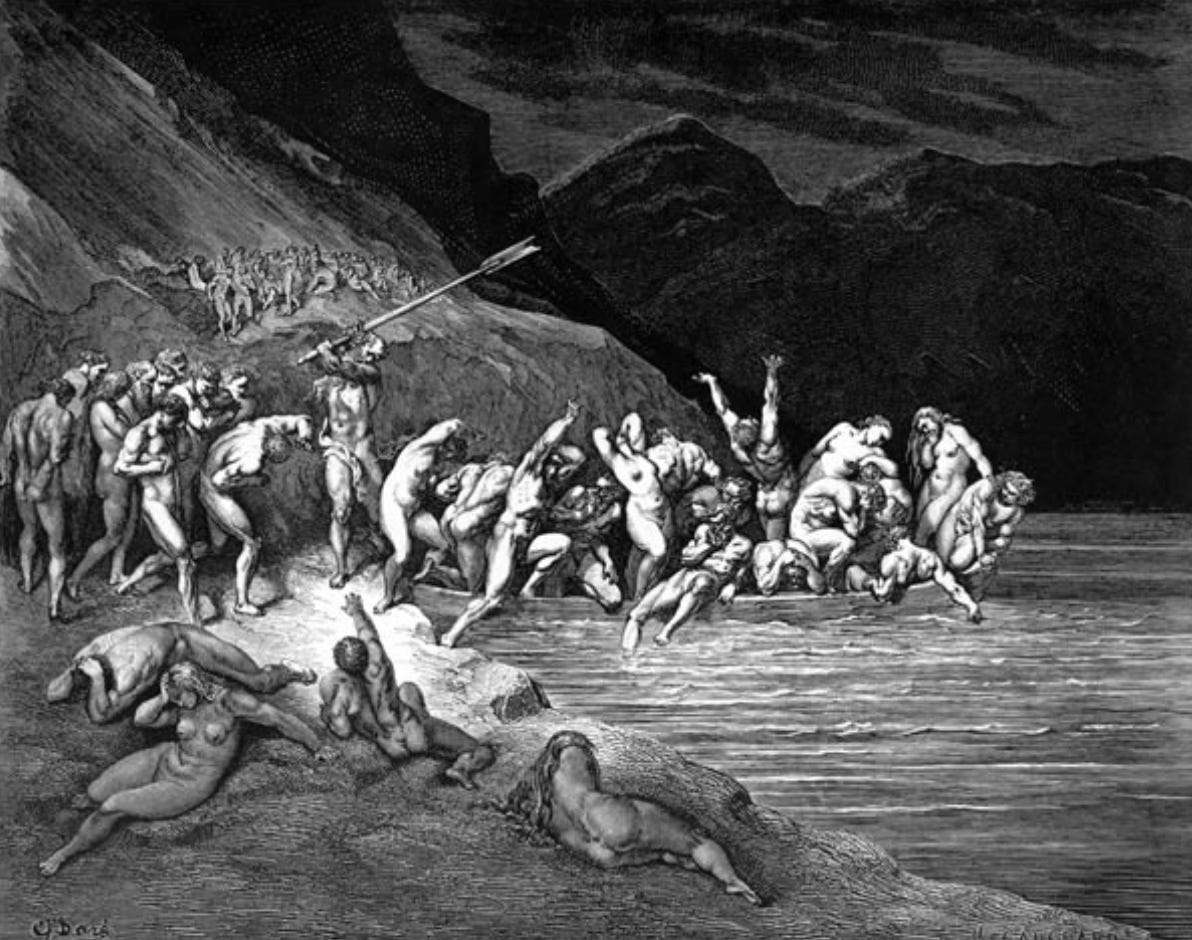

Charon and the Crossing of Acheron

The appearance of Charon, the boatman who ferries souls across the river Acheron, introduces an element of classical mythology into Dante's Christian Hell. Charon is described in terrifying terms:

"And lo! towards us coming in a boat

An old man, hoary with the hair of eld,

Crying: 'Woe unto you, ye souls depraved!'"

Charon initially refuses to take Dante, a living soul, across the river: "By other ways, by other ports / Thou to the shore shalt come, not here, for passage." This emphasizes Dante's unique status as a living visitor to the realm of the dead, foreshadowing the unique nature of his journey.

The souls' eagerness to cross into Hell proper is both surprising and disturbing:

"As in the autumn-time the leaves fall off,

First one and then another, till the branch

Unto the earth surrenders all its spoils;In similar wise the evil seed of Adam

Throw themselves from that margin one by one,

At signals, as a bird unto its lure."

This simile comparing the damned souls to falling leaves creates a haunting image of their vast numbers and their helplessness before divine judgment, emphasizing the overwhelming nature of divine justice.

The canto ends with a dramatic earthquake and a flash of light that causes Dante to faint, underscoring the intensity and gravity of his journey into Hell - "The land of tears gave forth a blast of wind, / And fulminated a vermilion light, / Which overmastered in me every sense, / And as a man whom sleep hath seized I fell."

This supernatural event marks the gravity of Dante's crossing into Hell proper. His loss of consciousness serves as a narrative device to transport him across Acheron; but also symbolizes the overwhelming nature of his spiritual journey.

Reflections on Sin, Justice, and Free Will

Canto III raises profound questions about the nature of sin, divine justice, and human free will. The punishment of the morally neutral challenges simplistic notions of good and evil, suggesting that failure to actively pursue virtue can be as damning as overt sin. This presents a call to moral engagement and conviction that remains deeply relevant.

The vast numbers of the damned - from the apathetic souls in the vestibule to the hordes crossing Acheron - paint a sobering picture of human fallibility. Yet the inscription on Hell's gate, attributing its creation to divine "Justice" and "primal love," complicates their simple notions of punishment. Dante suggests that even Hell serves God's ultimate purposes, though the nature of those purposes remains mysterious.

The eagerness of souls to enter Hell, despite knowing what awaits them, raises challenging questions about free will and the nature of sin - Are these souls compelled by divine justice, or do they, in some sense, choose their fate through their actions in life? The interplay between divine predestination and human choice will remain a central theme throughout the Divine Comedy.

Closing Thoughts

Canto III is a powerful opening to Dante's journey through Hell. It establishes key themes, introduces important characters like Charon, and presents challenging moral and theological concepts that will be explored throughout the Inferno. The vivid imagery - from the inscription on Hell's gate to the souls falling like autumn leaves - creates an unforgettable vision of the afterlife that has captivated readers for centuries.

As Dante loses consciousness at the canto's end, we readers are left to contemplate the weighty questions raised:

What does it mean to live a life of moral conviction?

How do we understand divine justice in the face of eternal punishment?

And how will Dante—and we as readers—be transformed by the journey ahead?

With these questions echoing in our minds, we prepare to descend further into the circles of Hell.

“Be at peace among yourselves. And we exhort you, brethren, admonish the idle, encourage the fainthearted, help the weak, be patient with them all. See that non of you repays evil for evil, but always seek to do good to one another and to all. Rejoice always, pray constantly, give thanks in all circumstances; for this is the will of God in Christ Jesus for you. Do not quench the Spirit, do not despise prophesying, but test everything; hold fast what is good, abstain from every form of evil.”

- The First Letter of St. Paul to the Thessalonians, 5:13-22