Baseball's Pythagorean Theorem

Predicting a team’s performance over the course of a season can be a complex task. While traditional statistics such as wins, losses, batting average, and ERA have been used, there are more insightful approaches. One approach lies in understanding the relationship between a team’s runs scored and runs allowed, which can be quantified through what is known as Baseball’s Pythagorean Theorem.1

Origins and Formula

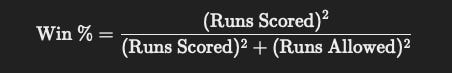

The term Pythagorean may sound familiar. For a few, it reminds us of Pythagoras of Samos, the ancient Greek philosopher; for most, it’s a reminder of high school geometry - the Pythagorean Theorem, which is used to establish a mathematical relationship between the lengths of the sides in a right triangle. However, in the context of baseball, it was coined by the pioneer of Sabermetrics, Bill James2. He observed that the ratio between a team’s runs scored (offensive capability) and runs allowed (defensive capability) could be used to predict their winning percentage. The formula is as follows:

This equation, like the Pythagorean theorem, involves squaring two values—runs scored, and runs allowed—which reflects the importance of both scoring and preventing runs in determining the outcome of games.

Why It Works

The formula is pretty intuitive for several reasons:

Runs Matter - the more runs a team scores, the more likely they are to win. Conversely, the fewer runs a team allows, the more likely they are to prevent losses.

Symmetry of Squaring - by squaring both runs scored and runs allowed, the formula magnifies large differences, which makes it more sensitive to teams that have high-scoring games but also high run allowances.

Prediction Range - the formula ensures that the predicted win percentage is always between 0 and 1, which aligns with how winning percentages are measured in baseball.

Example

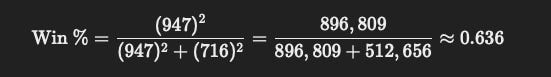

Consider the 2023 Atlanta Braves: The Braves scored 947 runs and allowed 716 runs over the course of the season. Here’s how the Baseball Pythagorean Theorem would be applied in this case:

This result predicts that the Braves will win approximately 63.6% of their games. In reality, the Braves had a winning percentage of 64.2%, which closely matches the prediction. They finished the season with a record of 104- 58, clinching the NL East Championship.

Why Does This Matter?

The value of Baseball’s Pythagorean Theorem is that it provides a tool for analyzing how well a team should have performed compared to how they actually performed. This insight can be particularly useful when evaluating teams with unusual discrepancies between their win-loss record and their run differential (the difference between runs scored and allowed).

For instance, if a team scores a lot of runs but ends up with a disappointing winning%, this could indicate that the team’s bullpen is giving up too many runs in high-leverage situations, or something similar in nature. On the other hand, a team that wins more games than their run differential suggests they could be benefiting from “luck” (or what I would call ‘randomness’…more on that at another time) in close games.

Refinements and Exponent Variation

While Bill James’ original formula used an exponent of 2 for the runs scored and runs allowed, further analysis has shown that tweaking the exponent can improve predictive accuracy. For baseball, an exponent closer to 1.83 often gives a more accurate prediction of the winning percentage. The reason for this is because…

Sensitivity to Run Scoring Environments - Baseball’s scoring environment isn’t perfectly symmetrical, and the actual relationship between runs scored, runs allowed, and winning percentage is slightly non-linear. The exponent of 2.0 is a simplification of this relationship. However, after analyzing large datasets of baseball games, sabermetricians discovered that an exponent closer to 1.83 better reflects how runs translate to wins across a wide range of scoring environments. This fine-tuning makes the model more sensitive to the run differential, resulting in more accurate win predictions.

Empirical Adjustments - The Pythagorean formula was originally developed as a heuristic, and while it performed well, subsequent analysis showed that lowering the exponent slightly to around 1.83 minimized prediction errors over a large sample size. This adjustment accounts for the fact that a smaller difference in runs scored and runs allowed may have a larger impact on a team’s winning percentage than the exponent of 2.0 suggests. In other words, teams that are slightly better at scoring more runs than they allow tend to win more often than the original formula predicts, and an exponent of 1.83 adjusts for this.

Variability in Team Performance - In a typical baseball season, there are variations in how teams perform in terms of run prevention and run production, and these variations are not perfectly proportional. The lower exponent makes the formula slightly more forgiving for teams that win with smaller run differentials, better aligning the predictions with the actual distribution of wins and losses across teams.

Statistical Fit - Ultimately, the shift to 1.83 comes from optimizing the formula through statistical analysis. By testing different exponents on historical data, researchers found that 1.83 consistently produced lower mean absolute error (MAE) when compared to actual winning percentages. This means the model better fits the observed data when this slightly lower exponent is used.

Points of Fragility

The best analysts are not the ones who use the best models; the best analysts are the ones who understand where the model is most fragile, and despite the high-quality performance of the Pythagorean Theorem, there are still points of fragility one needs to know about when applying it.

Luck in Close Games - One key blind spot is that the formula doesn’t account for how teams perform in close games. A team that consistently wins or loses many one-run games can deviate significantly from its expected win percentage. These games often hinge on factors such as bullpen management, clutch hitting, or situational defense, none of which the model considers. This can lead to a discrepancy between the predicted and the actual performance of teams that are particularly strong or weak in high-pressure situations.

Impact of Injuries and Roster Changes - The model is based on aggregate data over a season, but it cannot adjust for major in-season events like injuries or trades. If a key player gets injured for a significant portion of the season or if a midseason trade dramatically improves or weakens the roster, the Pythagorean formula will not account for these changes, potentially leading to misleading predictions - so it requires one to be hyper-vigilant when changes happen.

Run Distributions - The Pythagorean Theorem looks at the total number of runs scored and allowed but doesn't consider the distribution of those runs across games. A team that wins by large margins in few games but loses many close games might end up with a win-loss record that deviates from the predicted percentage. For example, a team could score 20 runs in one game and get shut out the next, resulting in a misleading estimate from the model.

Postseason Predictions - while the model can be highly effective for the regular season, its ability to predict outcomes in the playoffs is more limited. Playoff series are shorter and often involve only the best teams, where factors like starting pitcher depth or bullpen effectiveness play a larger role than over a long regular season. It’s also harder to model player performance in the postseason because many players in the postseason don’t have a large sample of played games that deep into the year.

I would highly recommend the book Mathletics, which covers this better than I will.

Bill James debuted the Baseball Pythagorean Theorem in the 1981 Baseball Abstract.